On covers, compilations, and community by Justin Remer

Singer/songwriter Dan Costello ran a weekly open mic in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, before the COVID-19 pandemic. Now, he is on the verge of celebrating one year of hosting the weekly virtual Open Mic Zoomburg, so named because the participants and listeners meet on Zoom. (Also, it rhymes with the name of former NY mayor Mike Bloomberg.)

Each week, Costello offers a theme that open mic-ers can try to use as a guide. "Sorry / Not Sorry" and "Stuff ___ Would Say" are examples. But closing in on that one-year anniversary, Costello decided to get nostalgic.

For years, there had been a tradition at the Lower East Side's Sidewalk Cafe, Costello's former stomping grounds, called "I Heart U." According to Costello, it was started by Benjamin Krieger. Krieger had taken over booking and open mic hosting duties from Lach, the self-styled "Godfather of Antifolk" responsible for making the Monday night open stage at Sidewalk a rite of passage for all self-respecting New York singer/songwriters.

At an I Heart U night, performers were required to play cover songs. But not Dylan or Joni or, god forbid, "Hallelujah." You had to cover someone else on the scene, or, in the very least, a not-famous songwriter you knew personally. Leonard Cohen doesn't need the publicity, after all. At an I Heart U open mic, performing an Antifolk cover bought you additional stage time to then play a song of your own. But the concept was popular enough that full-length I Heart U sets would get booked on regular nights and during the semi-annual Antifolk Festival.

At that recent "I Heart U"-themed Open Mic Zoomburg, over a dozen performers showed up to pay tribute to the music of other performers, many of whom were also present in the Zoom meeting. Performers cover songs for various reasons -- a familiar song can garner more attention, the song covered might be an uncanny fit for an artist's style -- but these performers were motivated simply to share their appreciation for the inspiration that their peers had provided them.

The Antifolk community in New York (AFNY for short) is like a lot of regional music scenes. Different artists and bands come together because they have the same sound and style -- or at least attitude. Antifolk was founded in a spirit of rebellion against the stodgy gatekeepers in New York who rose to prominence in the '60s but were still determining in the '80s what could be played in a "folk" club or at a "folk" event. Hence, "Antifolk." At an AFNY show, the audience might hear earnest acoustic music, irreverent rock à la Ween, lo-fi hip hop, or even just squalling psychedelic noise.

Singer/songwriter Dan Costello ran a weekly open mic in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, before the COVID-19 pandemic. Now, he is on the verge of celebrating one year of hosting the weekly virtual Open Mic Zoomburg, so named because the participants and listeners meet on Zoom. (Also, it rhymes with the name of former NY mayor Mike Bloomberg.)

Each week, Costello offers a theme that open mic-ers can try to use as a guide. "Sorry / Not Sorry" and "Stuff ___ Would Say" are examples. But closing in on that one-year anniversary, Costello decided to get nostalgic.

For years, there had been a tradition at the Lower East Side's Sidewalk Cafe, Costello's former stomping grounds, called "I Heart U." According to Costello, it was started by Benjamin Krieger. Krieger had taken over booking and open mic hosting duties from Lach, the self-styled "Godfather of Antifolk" responsible for making the Monday night open stage at Sidewalk a rite of passage for all self-respecting New York singer/songwriters.

At an I Heart U night, performers were required to play cover songs. But not Dylan or Joni or, god forbid, "Hallelujah." You had to cover someone else on the scene, or, in the very least, a not-famous songwriter you knew personally. Leonard Cohen doesn't need the publicity, after all. At an I Heart U open mic, performing an Antifolk cover bought you additional stage time to then play a song of your own. But the concept was popular enough that full-length I Heart U sets would get booked on regular nights and during the semi-annual Antifolk Festival.

At that recent "I Heart U"-themed Open Mic Zoomburg, over a dozen performers showed up to pay tribute to the music of other performers, many of whom were also present in the Zoom meeting. Performers cover songs for various reasons -- a familiar song can garner more attention, the song covered might be an uncanny fit for an artist's style -- but these performers were motivated simply to share their appreciation for the inspiration that their peers had provided them.

The Antifolk community in New York (AFNY for short) is like a lot of regional music scenes. Different artists and bands come together because they have the same sound and style -- or at least attitude. Antifolk was founded in a spirit of rebellion against the stodgy gatekeepers in New York who rose to prominence in the '60s but were still determining in the '80s what could be played in a "folk" club or at a "folk" event. Hence, "Antifolk." At an AFNY show, the audience might hear earnest acoustic music, irreverent rock à la Ween, lo-fi hip hop, or even just squalling psychedelic noise.

Because Antifolk is more of an attitude than a sound, it has always been difficult to explain the scene to interested listeners and journalists. Maybe that's the reason that there have been so many compilations released from the Antifolk community over the years, as different labels and curators try to sum up their vision of this slippery scene: "If you want to get it, just listen to it!"

The best-known of these compilations, Antifolk, Vol. 1, was curated by breakout Antifolk stars Kimya Dawson and Adam Green (aka The Moldy Peaches) and released by Rough Trade. But there have been many other offerings: A.S.S.: Art Star Sounds, Call It What You Want This Is Antifolk, Up the Anti- (from the Antifolk scene in the UK and Ireland), and Dan Costello even co-curated a two-disc collection once called Anticomp Folkilation.

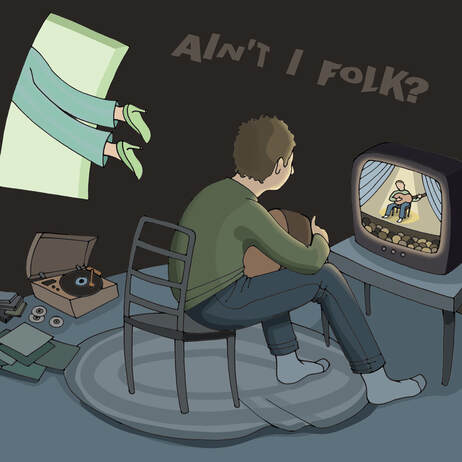

I knew this history when I decided to put together a compilation album of Antifolk artists covering other Antifolk artists. However, my intention in compiling Ain't I Folk? Weemayk Music Covers Antifolk Classics was not to make a definitive document of the scene like those other albums had attempted. I just wanted to highlight some interesting recordings already released by the teeny tiny record label I run, Weemayk Music. Admittedly, that might turn out a little bland, so I reached out to old collaborators and friends from the scene to see if they had anything suitable to spice up the track list.

I was quickly overwhelmed. Some artists had old unreleased recordings at the ready. Others had songs they always wanted to record that they would quickly whip together. I capped the album at 25 tracks, but as word-of-mouth about the project spread through the Antifolk community, it soon became apparent that I could potentially put out numerous volumes of Ain't I Folk? down the road. (Maybe I will.)

Even with this purposefully limited scope, I was happy to witness artists from the scene being covered and then paying it forward by covering someone else. Nan Turner (of the bands Schwervon! and Nan + the One Night Stands) delivers a moody cover of the ballad "I Don't Get Love" by Little Cobweb (aka Angela Carlucci of the rock duo True Dreams). Carlucci responded to the news that she was going to be covered on this album by picking a song by her brother Toby Goodshank, "No End 2 Shallow," and giving it an unusual but heartfelt redux. Elsewhere, Nan Turner's band Schwervon! is covered by a group that has shared numerous bills with them, Kung Fu Crimewave.

Similarly, when I messaged Dan Penta to ask if it was okay to include Brook Pridemore's cell-phone-recorded cover of "Low and Wet," a song that originates from Penta's days performing as Cockroach, Penta was not only okay with it, he immediately starting spitballing options for what great tune he could cover in return. He settled upon the French brother act, Herman Düne, and their "Futon Song." (The performance is credited to Cucaracha.)

It's kind of a joke that the person who curates an album does so just to include their own work, but the fact that I have included recordings of me performing songs by other people whom I love, respect, and admire feels a little less self-serving. (A little.) When I was with my old group Elastic No-No Band, I recorded covers by my collaborators Major Matt Mason USA and Thomas Patrick Maguire that are included on Ain't I Folk?.

I had met Major Matt (real name: Matt Roth) because he had a recording studio set up in his Lower East Side apartment that was a go-to spot for many Antifolk performers. Together, we produced three albums (give or take some songs) over the course of six years and I became a lifelong fan. In the days when I would ride the New York subway with a portable CD player as my main company, Major Matt's stripped-down debut Me Me Me was frequently spun. I started playing the bitter break-up song "Goodbye Southern Death Swing" on repeat, not because I was on the outs with anyone, but because I was in awe of the writing. My version is faster than Roth's recording, but I tried to maintain (alright... steal) some of the nuances of Roth's performance in mine.

When I was shut in during the early days of the pandemic, Major Matt provided me inspiration again. He posted a reflective video, in which he discussed what led to him writing "1,000 Ice Creams," a song whose surreal images of isolation and alienation, coupled with the description of music as a coping mechanism, hit bull's-eyes in my head and my heart. I did a bedroom recording of the song and released it under my new moniker Duck the Piano Wire. Then, my version inspired a musician in Germany, Sven Safarow, to do his own version of "1,000 Ice Creams" for his Youtube Channel called Quarantine Kitchen Covers.

Sven Safarow then fell down a tiny Antifolk covers hole. He recorded a new version of the song "Turn Out Right" from my old group Elastic No-No Band, which I put as the opening track of Ain't I Folk? (hey, I already said curators are biased!). He also recorded nearly a dozen songs by singer/songwriter Thomas Patrick Maguire, whose sensibility merges Billy Bragg with Kurt Cobain. Ain't I Folk? was already chock full of TPM covers (seven songs covered by three different artists), so Safarow's performances will be put out as a stand-alone album in the next few months.

Other artists on Ain't I Folk? include former subway busker Joe Crow Ryan, Staten Island duo Blurple, lo-fi fabulist Club Mate, animal-focused supergroup Urban Barnyard, the junkyard bohos of Huggabroomstik, '90s-alt-radio-influenced rockers The Telethons and chanteuse Gina Mobilio. No Pandora algorithm would likely lump them together on the same station, but there's an honest, offbeat spirit that all these acts share.

With most music venues and hang-out spots closed during the pandemic (and some, forever), musicians might be struggling to connect or find a nurturing creative community. Considering that context, the scattered members of the Antifolk diaspora are doing their best to stick together, even if it's just through a computer screen or some cover songs.

The best-known of these compilations, Antifolk, Vol. 1, was curated by breakout Antifolk stars Kimya Dawson and Adam Green (aka The Moldy Peaches) and released by Rough Trade. But there have been many other offerings: A.S.S.: Art Star Sounds, Call It What You Want This Is Antifolk, Up the Anti- (from the Antifolk scene in the UK and Ireland), and Dan Costello even co-curated a two-disc collection once called Anticomp Folkilation.

I knew this history when I decided to put together a compilation album of Antifolk artists covering other Antifolk artists. However, my intention in compiling Ain't I Folk? Weemayk Music Covers Antifolk Classics was not to make a definitive document of the scene like those other albums had attempted. I just wanted to highlight some interesting recordings already released by the teeny tiny record label I run, Weemayk Music. Admittedly, that might turn out a little bland, so I reached out to old collaborators and friends from the scene to see if they had anything suitable to spice up the track list.

I was quickly overwhelmed. Some artists had old unreleased recordings at the ready. Others had songs they always wanted to record that they would quickly whip together. I capped the album at 25 tracks, but as word-of-mouth about the project spread through the Antifolk community, it soon became apparent that I could potentially put out numerous volumes of Ain't I Folk? down the road. (Maybe I will.)

Even with this purposefully limited scope, I was happy to witness artists from the scene being covered and then paying it forward by covering someone else. Nan Turner (of the bands Schwervon! and Nan + the One Night Stands) delivers a moody cover of the ballad "I Don't Get Love" by Little Cobweb (aka Angela Carlucci of the rock duo True Dreams). Carlucci responded to the news that she was going to be covered on this album by picking a song by her brother Toby Goodshank, "No End 2 Shallow," and giving it an unusual but heartfelt redux. Elsewhere, Nan Turner's band Schwervon! is covered by a group that has shared numerous bills with them, Kung Fu Crimewave.

Similarly, when I messaged Dan Penta to ask if it was okay to include Brook Pridemore's cell-phone-recorded cover of "Low and Wet," a song that originates from Penta's days performing as Cockroach, Penta was not only okay with it, he immediately starting spitballing options for what great tune he could cover in return. He settled upon the French brother act, Herman Düne, and their "Futon Song." (The performance is credited to Cucaracha.)

It's kind of a joke that the person who curates an album does so just to include their own work, but the fact that I have included recordings of me performing songs by other people whom I love, respect, and admire feels a little less self-serving. (A little.) When I was with my old group Elastic No-No Band, I recorded covers by my collaborators Major Matt Mason USA and Thomas Patrick Maguire that are included on Ain't I Folk?.

I had met Major Matt (real name: Matt Roth) because he had a recording studio set up in his Lower East Side apartment that was a go-to spot for many Antifolk performers. Together, we produced three albums (give or take some songs) over the course of six years and I became a lifelong fan. In the days when I would ride the New York subway with a portable CD player as my main company, Major Matt's stripped-down debut Me Me Me was frequently spun. I started playing the bitter break-up song "Goodbye Southern Death Swing" on repeat, not because I was on the outs with anyone, but because I was in awe of the writing. My version is faster than Roth's recording, but I tried to maintain (alright... steal) some of the nuances of Roth's performance in mine.

When I was shut in during the early days of the pandemic, Major Matt provided me inspiration again. He posted a reflective video, in which he discussed what led to him writing "1,000 Ice Creams," a song whose surreal images of isolation and alienation, coupled with the description of music as a coping mechanism, hit bull's-eyes in my head and my heart. I did a bedroom recording of the song and released it under my new moniker Duck the Piano Wire. Then, my version inspired a musician in Germany, Sven Safarow, to do his own version of "1,000 Ice Creams" for his Youtube Channel called Quarantine Kitchen Covers.

Sven Safarow then fell down a tiny Antifolk covers hole. He recorded a new version of the song "Turn Out Right" from my old group Elastic No-No Band, which I put as the opening track of Ain't I Folk? (hey, I already said curators are biased!). He also recorded nearly a dozen songs by singer/songwriter Thomas Patrick Maguire, whose sensibility merges Billy Bragg with Kurt Cobain. Ain't I Folk? was already chock full of TPM covers (seven songs covered by three different artists), so Safarow's performances will be put out as a stand-alone album in the next few months.

Other artists on Ain't I Folk? include former subway busker Joe Crow Ryan, Staten Island duo Blurple, lo-fi fabulist Club Mate, animal-focused supergroup Urban Barnyard, the junkyard bohos of Huggabroomstik, '90s-alt-radio-influenced rockers The Telethons and chanteuse Gina Mobilio. No Pandora algorithm would likely lump them together on the same station, but there's an honest, offbeat spirit that all these acts share.

With most music venues and hang-out spots closed during the pandemic (and some, forever), musicians might be struggling to connect or find a nurturing creative community. Considering that context, the scattered members of the Antifolk diaspora are doing their best to stick together, even if it's just through a computer screen or some cover songs.